Sonographic imaging in uterine sarcoma: a narrative review of literature

Introduction

Uterine sarcomas include a heterogeneous group of tumors with an aggressive clinical behavior and poor prognosis. Sarcomas are rare and they represent 1% of all gynecological malignancies and 3–7% of all invasive uterine cancers (1). In the past, uterine sarcomas were classified into leiomyosarcomas, endometrial stromal sarcomas, carcinosarcomas and undifferentiated sarcomas. Recently, carcinosarcoma has been reclassified as a dedifferentiated or metaplastic form of endometrial carcinoma and it is staged using the endometrial carcinoma staging system (2). In according to 2011 Word Health Organization (WHO) classification, only low-grade endometrial stroma sarcoma is considered endometrial stroma sarcoma, while high grade endometrial stromal sarcoma is called undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma (3). In 2009 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging proposed two group: one for leiomyosarcomas and endometrial stroma sarcomas and one for adenosarcomas (1,4).

Median age at diagnosis, for all histological types of sarcoma, is 60 years old (5). Risk factors are advanced age and postmenopausal status (6). In the majority of uterine sarcomas diagnosis is incidentally carried out during surgery or at pathology in patients with sonographic suspicion of fibroids. More rarely diagnosis is achieved hysteroscopically of an intracavitary mass.

Pathological diagnosis of uterine sarcoma has always been difficult because many benign variants of smooth muscle tumors can simulate sarcomas, also ultrasound has difficulty in distinguishing a myoma from a sarcoma.

In past, several retrospective papers were published (7-19). These studies present few cases and ultrasound markers have never been coded. The correct differential diagnosis between benign myoma and sarcoma is mandatory for a correct surgical treatment.

In 2019 Ludovisi et al. published a series of 195 cases. This study proposes ultrasound markers associated with clinical symptoms and signs (7).

Due to the rarity of this condition, no prospective studies on the role of preoperative ultrasound have been performed. The objective of this review is to focus on the role of ultrasound in diagnosis of uterine sarcoma. We present the following article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-21-20/rc).

Methods

We searched publications related to the ultrasound diagnosis, clinical and pathological features of uterine sarcomas in PubMed, without time restrictions. Only studies in English were included. Full text of all articles was analyzed by three authors and after discussion, these authors selected the studies useful for the drafting of this work. Research on PubMed included: uterine sarcoma, ultrasound features, pathological features, diagnosis. We excluded studies that exclusively treated uterine carcinosarcomas, because they have been reclassified as a dedifferentiated form of endometrial carcinoma.

Discussion

According to 2011 Word Health Organization (WHO) sarcomas comprise three main histotypes (leiomyosarcoma, endometrial stroma sarcoma, and undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma) that have some characteristics in common but, at the same time, they differ from each other.

Leiomyosarcoma

Leiomyosarcomas result the most common subtype of uterine sarcomas, even if they represent only 1–2% of the malignant tumors of the uterus (20). The median age of women at diagnosis is 50–57years (3,7,21,22). Leiomyosarcomas have a poor prognosis even when diagnosed in the early stages. (4,23,24). Symptoms of leiomyosarcomas include abnormal uterine bleeding in pre- and post-menopause, pelvic pain, pressure, but these symptoms are the same as in benign myoma. Constipation and a foul-smelling vaginal discharge have been reported (5).

Leiomyosarcomas arise from a myometrial cell. Pathological diagnosis of leiomyosarcomas is difficult because the differential diagnosis includes all leiomyoma variants, that may mimic malignant lesions, atypical smooth muscle tumors (STUMPs). Furthermore, cellular pleomorphism of epithelioid and myxoid leiomyosarcomas, two rare variants, makes microscopic diagnosis difficult. In both tumors, nuclear atypia and mitotic rate are often low, moreover, myxoid leiomyosarcoma present often hypocellularity, while in epithelioid leiomyosarcoma, necrosis is rarely found (4,25,26). Leiomyosarcomas are more common in black women than in white women (21,6).

Endometrial stromal sarcoma

Endometrial stromal sarcomas are a rare tumor that represents only 0.2% of all malignant uterine neoplasms and they arise from the connective tissue of the endometrium. The median age of women with endometrial stromal sarcomas is 40–55years (3,21,22). In the series published by Ludovisi et al, patients with endometrial stromal sarcoma were younger than those with leiomyosarcoma or undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma (median age 46 vs. 57 vs. 60 years) and they were more often premenopausal (66.7% vs. 40.5% vs. 16.1%) (7).

The most frequent symptoms of endometrial stromal sarcomas are abnormal uterine bleeding and pelvic pain, but 10–25% of patients are asymptomatic (5,7). Endometrial stromal sarcomas are indolent tumors with a favorable prognosis. The 5-year disease specific survival for stage I and II tumors are 90% compared to 50% for stage III and IV (4,27).

Long-term exposure to tamoxifen (5 years or more) is associated with an increased risk of endometrial stromal sarcoma however, the absolute risk is low (28-30). The exposure to high levels of estrogen or pelvic radiation and polycystic ovary syndrome have been related to endometrial stromal sarcoma (3,31). Progesterone and aromatase inhibitors are often used to treat this disease, because endometrial stromal sarcomas present hormone receptors (32).

Undifferentiated stromal sarcoma

Undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas are more frequent in postmenopausal patients (4,7) and the mean age at diagnosis is 55–60years for undifferentiated stromal sarcoma (7,21,22). In 40–60% of cases, the diagnosis is performed at III–IV stage. Undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas are highly aggressive tumors with a very poor prognosis and most patients die of the disease within 2 years from diagnosis (4,7,25). The most frequent symptoms are postmenopausal bleeding and symptoms secondary to extrauterine spread (4).

Ultrasound features

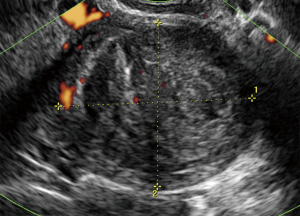

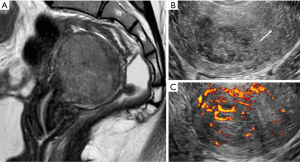

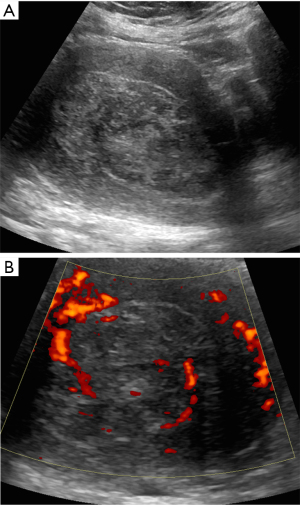

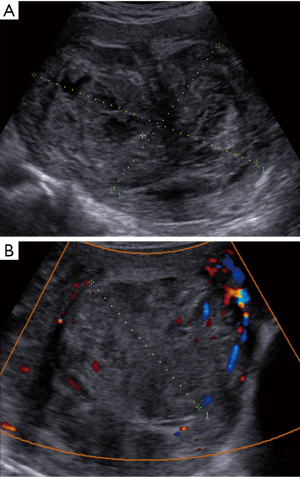

The correct preoperative diagnosis is most important, because an incorrect treatment such as morcellation of the sarcoma or tumor-positive resection margins significantly worsens the prognosis (33). Correct preoperative diagnosis of sarcoma may be difficult. Ultrasound examination, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography and positron emission tomography are not reliable in all cases (Figure 1). Ultrasound examination is the first approach, because ultrasound examination is easy to perform, requires no preparation and it is low cost. Symptoms and ultrasound features are often confused with those of benign uterine lesions (uterine myoma) or of other neoplastic lesions (endometrial cancer). In Figure 2 is shown an image of a leiomyosarcoma with ultrasound features of a benign lesion (Figure 2). The first large published series has described the clinical and ultrasound characteristics of 195 sarcomas (7), before several studies were published, but they described few cases, for example, the largest published series of leiomyosarcomas includes eight cases (8). In these studies, the ultrasound variables evaluated were different and often leiomyosarcomas, endometrial stromal sarcomas and undifferentiated stromal sarcomas were not described separately (8-19). In agreement with Exacoustos, Ludovisi et al. described that leiomyosarcomas are large (largest diameter 106 mm) and solitarian lesion, even if they may coexist in same uterus with benign myomas. Leiomyosarcomas are solid mass with inhomogeneous echogenicity with irregular border and irregular cystic areas in half of the cases. Vascularization was minimal or absent in one third of the leiomyosarcomas, in contrast to previous publications (8), probably linked to intra-lesional necrosis (Figures 3,4). Intravenous contrast-enhanced color flow Doppler is an emerging technique in gynecological ultrasound. A prospective study by Lieng suggest that intravenous contrast may help to discriminate between benign endometrial polips and cancer (34). A recent pilot study on a small cohort of patients (35) investigated the use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for the differential diagnosis of uterine leiomyoma subtype and sarcoma. This study describes an uneven high enhancement without regular border associated with large areas of non-enhancement for sarcomas. Ludovisi et al. introduced a new parameter to describe solid tissue necrosis, defined as “cooked appearance”, a homogeneous avascular area with blurred borders (7) (Figure 5). Exacoustos et al. compared ultrasound features of cellular leiomyomas with those of uterine sarcomas and they demonstrated ultrasound characteristics of “classic” leiomyomas and cellular leiomyomas are different from those of leiomyosarcomas.

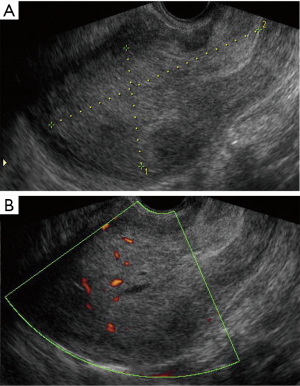

The largest published series describing the ultrasound features of endometrial stromal sarcoma includes 48 cases (7) and ten cases (11,17). Kim described 4 patterns of sonographic appearance of endometrial stromal sarcomas: a polypoid mass, an intramural mass, an ill defined large central cavity mass or diffuse myometrial thickening (17). Park described endometrial stromal sarcomas as solid masses with a mean size of 6.2 cm and with internal cystic degeneration in many cases (11). In the series published by Ludovisi et al., endometrial stromal sarcomas appeared solid masses (89.6%) with regular borders (60.4%) and inhomogeneous tissue. This type of sarcoma was less vascularized than the other sarcomas (color-score of 1–2 in 42.6%) (Figure 6).

Undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas appeared as solid, inhomogeneous lesions with an average diameter of 70 mm, with irregular border and rich vascularization (7).

Leiomyosarcomas, endometrial stromal sarcomas and undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas rarely have internal shadows and fan shaped shadowing (9,36). In a series of 23 uterine malignant myometrial tumors (three leiomyosarcomas, one rhabdomyosarcoma, two endometrial stromal sarcomas, seven undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas, four smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential, and six carcinosarcomas) lesions have been most frequently described as a single mass with no acoustic shadowing (9). Ludovisi et al. described internal shadows in about 20% of the sarcomas, while fan shaped shadowing was found more rarely. Calcifications were present in 10% of sarcomas (7). Similarly, Bonneau et al. described ultrasound signs of calcifications in 16% of sarcomas (9).

In all types of uterine sarcoma, free fluid in pouch of Douglas was rarely found and only 2% of cases had ascites (7).

The correct diagnosis was made in approximately 80% of the 195 sarcomas and undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas were correctly diagnosed in 93% of cases. Sarcomas were classified as benign leiomyoma in 14% of cases (7).

Conclusions

In this review of literature, there is agreement on clinical symptoms, while there is disagreement on ultrasound characteristics. In all publications, where clinical manifestations were evaluated, approximately 90% of patients had symptoms. Abnormal vaginal bleeding and abdominal-pelvic pain were the most frequent symptoms. Most of the patients with leiomyosarcoma and undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma are in menopause, while those with endometrial stromal sarcoma are in premenopause in more than half of the cases. From the literature, undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas are more often recognized as malignant, while leiomyosarcomas and endometrial stromal sarcomas are diagnosed as benign in one fifth of cases. Misdiagnosis of benign myoma of 14% is probably due to the vast heterogeneity of both benign and malignant uterine mesenchymal lesions as described by the pathologies, in particular the epithelioid and myxoid variant of leiomyosarcomas. In disagreement with Exacoustos et al. the vascularization of leiomyosarcomas was not abundant in about 35% of cases published by Ludovisi et al, this difference is probably due to the different size of the sample. The poor vascularisation could be justified by the presence of extensive internal necrosis. Solid tissue necrosis, defined as “cooked appearance”, should be sought whenever a lesion appears poorly vascularized.

Fan shading is a constant feature of leiomyomas. In our opinion, the most important aspect that emerges in the series published by Ludovisi et al. is the absence of the shadow cones in particular the absence of fan shaped shadowing in all types of sarcomas, especially in leiomyosarcomas, in according to Bonneau et al.

In conclusion, all large inhomogeneous uterine lesions with irregular cystic areas, without shadows and calcification in symptomatic patients especially with abnormal vaginal bleeding suggests malignancy. Preoperative diagnosis of sarcomas remains difficult. The correct preoperative diagnosis is essential for correct treatment. All mesenchymal lesions presenting dubious ultrasound features and clinical symptoms should be evaluated by experienced staff and only selected mesenchymal lesions should be sent to the reference centers.

The correct ultrasound diagnosis of benign and malignant lesions of myometrial tumors would be very interesting to evaluate with a prospective study especially stressing the evaluation of the shadow cones however, the rarity of these tumors makes it difficult to carry out this project.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Gynecology and Pelvic Medicine for the series “Uterine Sarcomas”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-21-20/rc

Peer Review File: available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-21-20/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-21-20/coif). The series “Uterine Sarcomas” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. AMP served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series and serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Gynecology and Pelvic Medicine from August 2020 to July 2022. PDI served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- D'Angelo E, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas:a review. Gynecol Oncol 2010;116:131-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prat J. FIGO staging for uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;104:177-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zaloudek CJ, Hendrickson MR, Soslow RA. Mesenchymal Tumors of the Uterus. In: Kurman RJ, Hedrick Ellenson L, Ronnet BM (eds). Blaustein’s Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. New York: Springer Science Business Media LLC, 2011:453-527.

- Prat J, Mbatani N. Uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131:S105-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang KL, Crabtree GS, Lim-Tan SK, et al. Primary uterine endometrial stromal neoplasms. A clinicopathologic study of 117 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14:415-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hosh M, Antar S, Nazzal A, et al. Uterine Sarcoma: Analysis of 13,089 Cases Based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2016;26:1098-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ludovisi M, Moro F, Pasciuto T, et al. Imaging in gynecological disease (15): Clinical and ultrasound characteristics of uterine sarcoma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;54:676-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Exacoustos C, Romanini ME, Amadio A, et al. Can gray-scale and color Doppler sonography differentiate between uterine leiomyosarcoma and leiomyoma? J Clin Ultrasound 2007;35:449-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonneau C, Thomassin-Naggara I, Dechoux S, et al. Value of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the characterization of uterine mesenchymal tumors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:261-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aviram R, Ochshorn Y, Markovitch O, et al. Uterine sarcomas versus leiomyomas: gray-scale and Doppler sonographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound 2005;33:10-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park GE, Rha SE, Oh SN, et al. Ultrasonographic findings of low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma of the uterus with a focus on cystic degeneration. Ultrasonography 2016;35:124-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hata K, Hata T, Maruyama R, et al. Uterine sarcoma: can it be differentiated from uterine leiomyoma with Doppler ultrasonography? A preliminary report. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1997;9:101-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Szabó I, Szánthó A, Papp Z. Uterine sarcoma: diagnosis with multiparameter sonographic analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1997;10:220-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adesiyun AG, Samaila MO. Leiomyosarcoma uteri in a white woman. Ann Afr Med 2010;9:35-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho FN, Liu CB, Yu KJ. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma initially manifesting as a large complex pedunculated mass arising from the uterine surface. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;38:233-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gandolfo N, Gandolfo NG, Serafini G, et al. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the uterus: MR and US findings. Eur Radiol 2000;10:776-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim JA, Lee MS, Choi JS. Sonographic Findings of Uterine Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma. Korean J Radiol 2006;7:281-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Montiel D, Salmeron AA, Domínguez Malagon H. Multicystic Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol 2004;8:213-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Somma A, Falletti J, Di Simone D, et al. Cystic Variant of Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma: Report of Two Cases. Int J Surg Pathol 2013;21:278-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giuntoli RL II, Metzinger DS, DiMarco CS, et al. Retrospective review of 208 patients with leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: prognostic indicators, surgical management, and adjuvant therapy. Gynecol Oncol 2003;89:460-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tropé CG, Abeler VM, Kristensen GB. Diagnosis and treatment of sarcoma of the uterus. A review. Acta Oncol 2012;51:694-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah SH, Jagannathan JP, Krajewski K, et al. Uterine sarcomas: then and now. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;199:213-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abeler VM, Royne O, Thoresen S, et al. Uterine sarcomas in Norway. A histopathological and prognostic survey of a total population from 1970 to 2000 including 419 patients. Histopathology 2009;54:355-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pelmus M, Penault-Llorca F, Guillou L, et al. Prognostic factors in early-stage leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2009;19:385-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oliva E, Carcangiu ML, Carinelli S, et al. Mesenchymal tumours. In: Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, et al. (eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. Lyons: IARC Press, 2014:135-47.

- Evans HL, Chawla SP, Simpson C, et al. Smooth muscle neoplasms of the uterus other than ordinary leiomyoma. A study of 46 cases with emphasis on diagnostic criteria and prognostic factors. Cancer 1988;62:2239-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan JK, Kawar NM, Shin JY, et al. Endometrial stromalsarcoma: a population-based analysis. Br J Cancer 2008;99:1210-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wysowski DK, Honig SF, Beitz J. Uterine sarcoma associated with tamoxifen use. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1832-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mourits MJ, De Vries EG, Willemse PH, et al. Tamoxifen treatment and gynecologic side effects:a review. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:855-66. [PubMed]

- Yildirim Y, Inal MM, Sanci M, et al. Development of uterine sarcoma after tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer: report of four cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005;15:1239. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gadducci A, Gargini A, Palla E, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and gynecological cancers: is there a link? Gynecol Endocrinol 2005;20:200-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi H, Uekuri C, Akasaka J, et al. The biology of uterine sarcomas: A review and update. Mol Clin Oncol 2013;1:599-609. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Food And Drug Administration. Laparoscopic Uterine Power Morcellation in Hysterectomy and Myomectomy. FDA Safety Communication (US), 2014.

- Lieng M, Qvigstad E, Dahl GF, et al. Flow differences between endometrial polyps and cancer: a prospective study using intravenous contrast-enhanced transvaginal color flow Doppler and three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;32:935-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu Y, Yuan K, Lin D, et al. A pilot study on the differential diagnosis of uterine leiomyoma subtype and sarcoma by contrast-enhanced ultrasound. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2021;47:311-9. [Crossref]

- Kliewer MA, Hertzberg BS, George PY, et al. Acoustic shadowing from uterine leiomyomas: sonographic-pathologic correlation. Radiology 1995;196:99-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Giunchi S, Perrone AM, Tesei M, Bovicelli A, De Crescenzo E, Dondi G, Boussedra S, Di Stanislao M, De Iaco P. Sonographic imaging in uterine sarcoma: a narrative review of literature. Gynecol Pelvic Med 2022;5:14.